Home » Jazz Articles » First Time I Saw » Connie Kay Plays the Drums Impeccably

Connie Kay Plays the Drums Impeccably

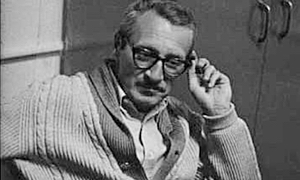

In all music, I don't think there's ever been anything quite like Connie Kay's cymbals. You could detect the ping of his ride cymbal out of a thousand—dry and metallic with just a hint of sizzle. Like the drop of vermouth in a dry martini. He must have used very special drumsticks, too, because they added a slightly hollow, "woody" timbre. His cymbals' sound was so full, he could play chorus after chorus and barely touch his snare drum, making it all work immaculately with just his high-hat and ride cymbal. Needless to say, Connie Kay was a major contributor to the brilliantly cool, totally unmistakable sound that was the Modern Jazz Quartet.

I first encountered him in person the night that the Modern Jazz Quartet was introduced on live TV on the old Steve Allen Tonight Show.

Allen was a great proponent of good jazz at a time when the world was falling in love with doo-wop and schlock. I was in the studio audience that night with a couple of my jazz cronies. Allen introduced the MJQ, explaining that their music was hard to categorize, that it was "chamber jazz," that it was improvised, but it was not like the big bands or the hard-bop groups holding sway with jazz audiences at the time.

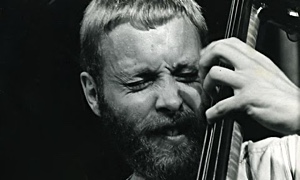

The lights went on at stage left, and the Quartet began with "I'll Remember April." The perfect balance, the fragile structure that contained the crystalline solos of John Lewis, and the rolling echoes of Milt Jackson's sensuous vibes, were all held together by the big woody tone of Percy Heath's bass and Connie Kay's immaculately swinging drums. Or to be more precise, his cymbals.

Connie Kay's drum kit not only sounded cool: it really looked cool. In addition to the standard gleaming black tubs, the snare, the tom-tom, the bass drum, the floor tom, and the burnished cymbals and twinkling bell tree, his set included two exotic-looking, matching, silver tom-toms mounted in front of him just below eye level. (I read somewhere that John Lewis, seeing these drums in a music store in some exotic place, had bought them for his esteemed drummer.)

But of course, Mr. Kay used them with the very greatest discretion and restraint. Just because they were there didn't mean he had to play them on every tune. When he did apply his fleecy mallets to them, the silver drums produced a soft, floating, muted kettle drum sound—tuned notes that blended in and out of Percy Heath's deep-bass phrases.

When the MJQ finished "April," there was a momentary silence before the audience broke into applause. This was not a sophisticated "jazz audience." They were the TV viewers of the late '50's. Not exactly people impressed by nuance. And yet this night, they were completely captivated by what they'd just heard. And felt.

The quartet came back again later in the show. They played "Willow Weep for Me"—all slow and bluesy—and Connie Kay's brush work sounded like willow branches swishing in a gentle wind.

After that night, I bought the MJQ's albums as soon as they came out. And I went to see them every chance I got—usually at the Village Vanguard, where you could hear Milt Jackson humming off key as he played, and where Connie Kay's cymbals became these dynamic solo instruments with all kinds of exotic, whispering voices.

I also heard them on a quiet spring afternoon at Town Hall, presented in concert like the brilliant jewels that they were. They played long, classically-structured pieces in which Connie Kay turned the silver, toy-like triangle into another high-pitched cymbal, balanced against the swinging clip-clip of his high-hat. The time feeling was just there—and so deeply felt inside the group that the music could go on bar after bar without ever literally stating the beat.

Connie Kay created ethereal magic with wood and stretched plastic, wire and pounded metal. What a wondrous miracle that he was there at the right time and in the right place not only to join but help create one of the great musical aggregations of all time—with his impeccable sound on the cymbals.

< Previous

Lullaby of Birdland

Comments

Tags

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.