Home » Jazz Articles » Touchstone Album Picks » Eddie Henderson: Everything Changes

Eddie Henderson: Everything Changes

Courtesy John Watson/Jazz Camera

If you study history, the music of any particular era reflects what is going on sociologically.

—Eddie Henderson

Yet Henderson has always been his own man. From Realization (Capricorn, 1973) to Witness To History (Smoke Sessions, 2023), Henderson has built an impressive career as a leader in his own right, with over two dozen albums to his name.

That he has always been able to call upon a heavyweight roster of musician for his projects is testament to the esteem in which his peers hold him.

But these achievements are only half the story. A qualified doctor and psychiatrist, Henderson holds the distinction of having been the first African American to compete for the American National figure-skating championship, winning two regional titles. In many ways, his has been a remarkable journey.

Perhaps it was written in the stars, after all, how many nine-year-olds take their first trumpet lesson from Louis Armstrong?

Now Henderson's life is the subject of a PBS documentary, Dr. Eddie Henderson: Uncommon Genius (2024). The recognition is overdue. At 83, Henderson is still touring, still recording, and sounding as good as ever.

Four Miles Davis titles in Eddie Henderson's six influential album picks suggest that the Illinois trumpeter was his primary influence, but that is not the case: "The most important musical influence over and above Miles was John Coltrane," Henderson explains. "The spirituality that he interjected into the music really started making me evolve as a musician and as a human being."

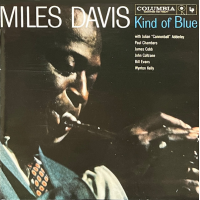

Miles Davis

Miles DavisKind of Blue

(Columbia)

1959

All About Jazz: Do you remember first hearing Kind of Blue, and how it sounded to you?

Eddie Henderson: When Miles was in San Francisco he just so happened to be staying at my parents' house. He gave my stepfather, who was his doctor, the original test pressing with grooves on one side and blank on the other side. To hear Miles, John Coltrane, Cannonball Adderley... that was my first awakening, my spiritual awakening to jazz music. It really had a profound effect on me, and that's why I do what I do at this present time.

AAJ: Has your appreciation of Kind of Blue changed over the years?

EH: Every time I hear it, even though it was done in '59, it sounds just like it was done in the present, or the future. It is such an iconic, important album in the evolution of quote unquote "jazz music." It just stands out in the crowd.

When Miles came out with that album it changed the whole trajectory of the music from bebop to that sort of open style sort of concept, rather than just a bunch of changes, back-to-back.

AAJ: A common denominator on three of your album picks is drummer Jimmy Cobb. Does Jimmy Cobb get the recognition he deserves for his role on Kind of Blue, and throughout his career in general?

EH: He doesn't. Jimmy Cobb, Wynton Kelly and Paul Chambers were the icing on the cake. They laid down the red carpet for Miles. I would speak to them off the bandstand and they would tell me, 'We made him sound good!' [laughing]. But speaking of Jimmy Cobb, he was a grand master. He was an essential, integral part of that rhythm section that laid the groundwork, the life-support system for how Miles Davis could play like that. That album and the people on it were really the spearhead, at that particular time, in changing the direction of music.

AAJ: You went on to play and record with Jimmy Cobb...

EH: He started hiring me for gigs, and it was really funny, because he told me he was going to do an album called Remembering Miles: Tribute To Miles [Eighty Eight's, 2011] and he wanted me to play the trumpet. What an honor! We get to the record date, I look around and I said, "Where's the saxophonist?" He said, 'No, it's just a quartet. You got it man.' I said, 'Whaaat!' [laughing].

It was beyond my wildest dreams. I first saw him with Miles when I was eighteen years old and now this man was hiring me to sit in that hot seat! [laughs]. It was more than an honor.

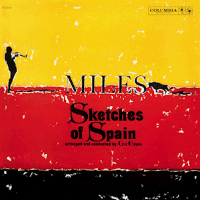

Miles Davis

Miles DavisSketches of Spain

(Columbia)

1960

AAJ: Miles Davis began recording Sketches of Spain just three months after Kind of Blue came out, and it is a unique album in his discography. At the time some called it 'Third Stream.' Miles said it was simply music. What is your take on this album?

EH: Yeah. It can't be categorized as jazz; it is just music. It's beautiful, universal music. When I met Miles Davis at my parents, they wanted me to play in front of him. So, I put this record on, and I played with the record verbatim, just like he played. I didn't miss a note. I went up to Miles, proud of myself, and I said, 'So, how did you like that?' Miles smiled and chuckled and responded by saying, 'You sound good, but that's me.' I thought, whoops! Clumsy me! [laughs].

AAJ: You have recounted before how Miles Davis encouraged you from that point to find your own voice. How much of a challenge was that, when you were a young man, trying to find your own, authentic voice?

EH: That's a wonderful question and I'm glad you asked that. When Miles Davis told me 'that's me,' I didn't see him again for another year when he came back and stayed at my parents' house. In that year interim I found out that his hero who he imitated, the sound, concept and phrasing, and all that stuff, was a guy named Freddie Webster. He wasn't that well known.

When Miles knocked on the door he said to me, 'Hey Eddie, you still trying to copy me?' I said, 'You mean Freddie Webster?' You should have seen the look on Miles' face! He said, 'Oh shit! I didn't know you was into that!' He smiles and whispers in my ear, 'Everybody's a thief. I just made a short-term loan.' [laughs].

You know, everybody comes from their predecessors. Miles Davis, Charlie Parker ... these people didn't just drop from the sky. They learned from those who came before them. That's the name of the game.

AAJ: Sketches of Spain is one of the few occasions where Miles Davis plays flugelhorn—an instrument you have played a fair amount. Were you surprised that he didn't play flugelhorn more often?

EH: Well... he had such a unique sound. As many times as I seen him live, I never saw him play the flugelhorn. You play the flugelhorn the same way, but the flugelhorn has a richer sound, a more mellow sound.

Listening to Miles and his sound on the trumpet, and then after I heard Freddie Hubbard and Lee Morgan, and I wanted to sound like them. So, bits and pieces of their personalities hopefully rubbed off on me. But it is about trying to get your own personal sound. That's the name of the game.

There are thousands of musicians all around the world playing the same instrument, but with one note you can tell its Miles Davis, or Charlie Parker, or John Coltrane. Or Nat King Cole. That's the sign of a true artist—one note, one phrase, and everybody knows who it is.

AAJ: What about Gil Evans' arrangements on this album? He was key, no?

EH Gil Evans's arrangement of that album was just heavenly. They brought Miles' sound to the forefront.

Miles Davis

Miles DavisSomeday My Prince Will Come

(Columbia)

1961

AAJ: This is one of Miles Davis' most romantic albums, but perhaps not one of his most celebrated. What drew you so strongly to this album?

EH: Just the way he plays melody. He takes his time, and it is enchanting. He makes the melody become a living entity. And he makes it believable. He goes right to the source of emotionality, and it touches you with immediate effect. I mean, he does that with almost all of his albums, but that album stands out from the crowd. I used to wear that record out until there were no more grooves [laughs].

AAJ: "I Thought About You," with Miles on mute, is particularly lovely.

EH: Oh my God! He could play a ballad so beautiful. I asked him one time, 'How can you pay a ballad so pretty?' And he said, 'Listening to singers like Nat King Cole, Sarah Vaughan, Billie Holiday ... and their delivery of the lyrics to make it a living presence.' That's exactly what he told me.

AAJ: There have been few better balladeers than Miles Davis, in my book.

EH True. I agree. You know, some people use vibrato, like Clifford Brown. Lee Morgan had a certain vibrato; Freddie Hubbard had a certain vibrato. But the thing that distinguished Miles Davis and that set him apart was that he used no vibrato. Herbie Hancock characterized Miles' sound as like looking out through a telescope into space and seeing a piece of ice-blue machine steel, like a monolith—it's ice cold, it's beautiful and warm at the same time [laughs].

AAJ: John Coltrane had left that band after the first recording session in March, so he's only on two tracks. Then, after trying Sonny Stitt and Jimmy Heath, Miles Davis settled on Hank Mobley. He had big shoes to fill, but he plays beautifully. How did you rate him?

EH: Oh, so melodic. He and Miles were great together. I saw Hank playing with Miles many times at the Blackhawk with that band.

AAJ: You recorded both "Old Folks" and "Someday My prince Will Come" on your album So What (Eighty Eight's, 2002) ...

EH: Oh yeah. I was just trying to pay homage to my influence of Miles Davis. But I tried to tell everybody, we've all heard the record but let's not try and do it like the record. Let's put it in the present tense. Everybody on that record rose to the occasion.

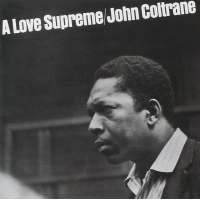

John Coltrane

John ColtraneA Love Supreme

(Impulse!)

1965

AAJ: This is John Coltrane's most commercially successful album. It is certainly his most famous studio recording, as well as his most discussed. Is there something extra-musical that accounts for the album's iconic status?

EH: Yes, yes. With Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie you had the bebop era. Before that there was the Dixieland era, then the swing era with the big bands. Miles changed the trajectory of the music with what the critics called cool jazz, or modal jazz. Then when John Coltrane came with A Love Supreme you could hear the spiritual element.

He had had a spiritual experience and he realized where it all came from—the almighty creator of everything. He really opened the door, at least in my mind when I first heard it. It was like a spiritual revelation. It showed the omnipotence of God, that you could express the universe through your instrument.

AAJ: Why did people respond so well to this album? Had it anything to do with the turmoil of the time, the Civil Rights struggle, the war in Vietnam? Was there perhaps a deep-seated need for this spirituality?

EH: Yes, I think so. If you study history, the music of any particular era reflects what is going on sociologically. Everything that was going on—the racial tension, the Vietnam war—it was a tumultuous time. That was reflected in John Coltrane's evolution, to become, with saving grace, a spiritual spearhead with A Love Supreme and go right back to God, where it all came from.

AAJ: You played and recorded with a lot of the musicians on the A Love Supreme sessions—Elvin Jones, Archie Shepp and McCoy Tyner ...

EH: Yeah, I recorded with McCoy's big band—what a thrill that was! I played in McCoy' quintet and sextet. I played in Elvin Jones' quintet and sextet ...

AAJ: Did they ever talk much about the whole A Love Supreme experience?

EH: No, not really. I wanted to ask them so much, you know, questions about Coltrane, but I just left that alone, out of respect for them. They all knew how much we appreciated everything they gave during that period. I didn't have to question them about it. The music spoke for itself.

AAJ: A Love Supreme clocked in at just under thirty-three minutes. Today, many CDs stretch to an hour, or even seventy minutes; Is that much music maybe a bit bloated, too much of a good thing?

EH: I know. Yes... I concur with that. Nowadays it's like they're trying to get a bunch of tunes in the can in the hope of getting a hit. They're maybe not thinking about the quality, or the concept of an album. A Love Supreme was not like that. It was truly from the soul. You can hear through the music that everybody on that record meant what they played.

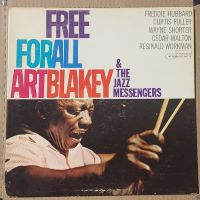

Art Blakey

Art BlakeyFree for All

(Blue Note)

1965

AAJ: Another incredibly powerful album. Art Blakey recorded a ton of albums with The Messengers, so why this particular one for you?

EH: I was in Washington DC at medical school, chasing Freddie Hubbard and Lee Morgan like a little puppy dog, [laughs] going to their houses and having lessons with them. I would go to every gig they had, chasing Art Blakey around, listening to that music.

The Free For All album was the epitome of that particular project, with Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Curtis Fuller, Cedar Walton, Reggie Workman and Art Blakey. It's one of my favorite albums of that type of music.

AAJ: There is that Freddie Hubbard song, "The Core," named for the Congress of Racial Equality; were organisations like that important for you in dealing with the racism that was so endemic?

EH: I didn't really see the forest for looking at the leaves of the trees. I was just chasing Freddie Hubbard and Lee Morgan around. I wasn't aware of all the sociological implications of The Congress of Racial Equality. I didn't realize the significance of all that until later.

AAJ: The chasing must have worked because you went on to play with Art Blakey's The Jazz Messengers ...

EH: Art hired me many times after I had played with Herbie Hancock. It was such a learning institution where all young musicians coming up during that time did their apprenticeship before going out on their own.

I played with Art Blakey in San Francisco, in L.A., Minneapolis, we played on the east coast also. I went to London with him for three weeks, one time too. Many different tours.

One was recorded, the very first time I played with The Messengers—it was at the Newport Festival in Central Park. Actually, Roy Haynes sat in on that concert. That was way back in 1973.

AAJ: As a drummer, Art Blakey was a one-off, wasn't he? He does this pressed roll near the start of "Free for All" that is absolutely thunderous. I don't think any drummer played with that intensity.

EH: You got that right [laughs]. Nobody played that pressed roll better than him.

AAJ: And those bass bombs!

EH: Oh yeah! He was a powerful person in the evolution of this music.

Miles Davis

Miles DavisBitches Brew

(Columbia)

1970

AAJ: Your final pick is an album that was divisive at the time, but which has only gained in influence as the decades have passed. Do you remember hearing Bitches Brew for the first time?

EH: I heard it about six months after it came out, which was just before I joined Herbie Hancock in the Mwandishi group. I think that concept of open-skies play, of everybody playing together like a collective conversation was the prototype of Herbie's Mwandishi concept. That album changed the trajectory of music at the beginning of the '70s.

AAJ: Bennie Maupin played bass clarinet on Bitches Brew and he would go on to play alongside you in Herbie Hancock's Mwandishi band...

EH: ...Bennie Maupin, Julian Priester, Billy Hart, Buster Williams and Herbie. It was the beginning of my professional career when I joined that band in 1970, and it has been like that ever since.

AAJ: A lot of jazz critics at the time reacted negatively to Bitches Brew. In fact, Nat Hentoff told me that his negative review of the album cost him his friendship with Miles Davis. Davis was also accused by some of selling out by playing rock music to attract the bigger, predominantly white audiences. Were such criticisms unfair, in your opinion?

EH: I certainly do think it was unfair. Those kinds of critics don't want to pass the baton. They don't want the music to change. They just want to hold it where they like it. People used to say the same sort of things when Dizzy Gillespie and Charlie Parker came in with bebop. But no matter what, everything changes.

< Previous

Introducing Pianist Tyler Bullock

Comments

About Eddie Henderson

Instrument: Trumpet

Related Articles | Concerts | Albums | Photos | Similar ToTags

Touchstone Album Picks

Eddie Henderson

Ian Patterson

Herbie Hancock

Art Blakey

Elvin Jones

Archie Schepp

Pharoah Sanders

McCoy Tyner

Louis Armstrong

Miles Davis

Cannonball Adderley

Jimmy Cobb

Wynton Kelly

Paul Chambers

Freddie Webster

Charlie Parker

Freddie Hubbard

lee morgan

Nat King Cole

Gil Evans

Sarah Vaughan

Billie Holiday

Clifford Brown

Sonny Stitt

Jimmy Heath

Hank Mobley

Dizzy Gillespie

Wayne Shorter

Curtis Fuller

BENNIE MAUPIN

Julian Priester

Billy Hart

Buster Williams

Nat Hentoff

negative review

Concerts

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.