Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » The Autobiography of Randy Weston: African Rhythms

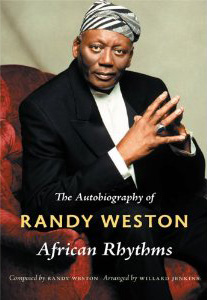

The Autobiography of Randy Weston: African Rhythms

The Autobiography of Randy Weston: African Rhythms

The Autobiography of Randy Weston: African RhythmsRandy Weston / Willard Jenkins

Hardcover; 344 pages

ISBN: 978-0-8223-4784-2

Duke University Press

2010

It's hard to think of another jazz musician who has promoted the African roots of jazz with quite the missionary zeal of pianist Randy Weston. Weston's African consciousness was awakened by his father, who taught his son that he was an African in Brooklyn. As this autobiography demonstrates, Weston's musical journey—indeed his entire philosophy—has been conditioned by this identity. Based on interviews conducted by Willard Jenkins over four years, this first person narrative documents not only Weston's illustrious career as one of the preeminent pianists and composers of the last 60 years, but also his tireless proselytizing of the glory of Mother Africa. What emerges is a picture of Weston as a champion of African—American culture, an activist who has spent his entire life speaking of the historical contribution of blacks to America and the rest of the world, and a musician whose every note is inspired by Africa and the resilience and dignity shown by his people in the face of slavery, segregation and racism.

Weston's portrayal of Brooklyn in the pre-war years is of a tight-knit black community where music of all kinds played day and night. The Second World War took Weston to Okinawa for a year and despite the efforts of Japanese snipers and ferocious typhoons, he emerged unscathed. However, the Brooklyn he paints in the aftermath of the war is one ravaged by alcohol and heroin, and Weston speaks of his move to the tranquility of the Berkshires in terms of a fortuitous escape.

In contrast to the moribund, drug-addled Brooklyn he left behind, the Berkshires provided Weston not only with a retreat, but with a life-changing encounter with Marshall Winslow Stearns, who was lecturing at the Music Inn there on the history of jazz. For the first time Weston heard of the West African roots of jazz and he was never to look back. The musical apprenticeship Weston earned in 10 summers there—playing in a trio and meeting a plethora of artistic folk—was of paramount importance: "I was able to reconcile myself to making music my profession," says Weston.

Weston provides colorful insight into the realities of life on the road in the US in the late 1940s, touring with saxophonist Bullmoose Jackson. Most memorable is a description of a battle of the bands in a Texas club where guitarist Lowell Fulsom's band—including a young Ray Charles on piano--- were standing on tables playing when Jackson's band walked in. As Weston recalls: "we got our butts thoroughly whipped that night." Ever present in the tales—though not dwelt overly upon—is the climate of racism pervasive in those days

The guts of the book recount Weston's relationship with Africa; his visits there in the first half of the 1960, his seminal big-band recording Uhuru Afrika (Roulette, 1960) arranged by the great Melba Liston, which was banned in apartheid-era South Africa, his memorable descriptions of hanging out in the company of Afrobeat originator Fela Kuti in Lagos, his nervousness at encountering a juju market, and the hallucinatory power of traditional African music. Weston describes a festival encountered on a trip to Nigeria in 1977; a month-long event culminated in 20,000 people celebrating the music of Fela Kuti, singers Stevie Wonder and Miriam Makeba and British Afro-rock band Osibisa; Weston laments: "The white press gave it absolutely no coverage."

Disillusionment with the avant-garde scene in New York and the incursion of electronics in jazz drove Weston to fulfill his dream of moving to Africa, and the six years he would spend in Morocco running a jazz club makes for interesting reading. Weston acknowledges that one of his greatest achievements was helping to bring national and international recognition to the local gnawa musicians; his association with these traditional musicians has continued up to this day.

Whether advocating black musicians' rights in the 1960s, recording with traditional African musicians in the 1990s or inaugurating the new Library of Alexandria in Egypt in the 2000s, the common thread which runs through African Rhythms is Weston's enduring love affair with African culture and its importance as the progenitor of jazz and pretty much everything else besides. This is an important addition to the jazz historiography and a long anticipated read for fans of this giant of African American music, aka jazz.

< Previous

Fragments

Comments

Tags

Randy Weston

Book Reviews

Ian Patterson

United States

Marshall Stearns

Ray Charles

Melba Liston

Fela Kuti

Stevie Wonder

Miriam Makeba

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.