Home » Jazz Articles » Book Review » Herman Leonard: Jazz

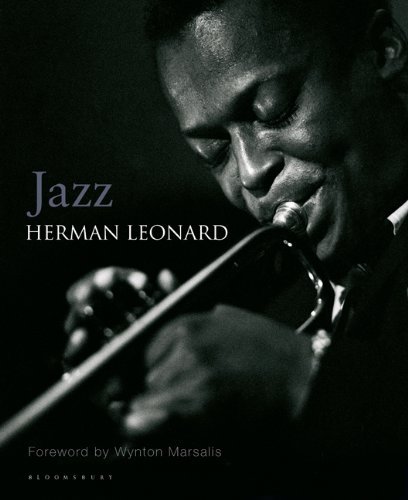

Herman Leonard: Jazz

Jazz

JazzHerman Leonard

Hardcover; 320 pages

ISBN: 9781848870741

Atlantic Books

2010

Jazz is billed as the definitive collection of photographer Herman Leonard's jazz photos. When record companies use ths term to promote box sets, appealing to the completist in many jazz fans, it is often not the case, and lo and behold, a few years later "newly unearthed" recordings emerge, much to the chagrin of those who shelled out first time around. In this case, however, so strikingly beautiful are Leonard's images that it would be nothing short of a gift if further volumes of his previously unpublished photography were to come to light.

It seems that plenty of such photos may exist. When Katrina struck in 2005, Leonard lost 10,000 prints and all his exposure records; however, to quote one of the stage announcers at Woodstock: "There's a little bit of heaven in every disaster area." For in assessing the damage prior to relocating to Los Angeles, and starting over at the age of 82, Leonard found previously unpublished photographs, many of which appear in this stunning book.

As you would expect, Leonard's defining photos from the 1940s and 1950s shot in Birdland and the Royal Roost are here: trumpeter Miles Davis backstage, trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie and alto saxophonist Charlie Parker in full flight, and that photo of tenor saxophonist Dexter Gordon which not only captured, but which went a long way to defining jazz cool; it is arguably as iconic a work of jazz art as many of the recordings that serve as benchmarks to this day.

There are more than 200 black and white photographs to pour over and every one tells a story or two. Atlantic Books have done an excellent job in reproducing these photographs. The quality of page and print is so good that you can almost smell the smoke curling up in just about every shot from half a century ago, or wipe the sheen of sweat off pianist Bud Powell's forehead, and, in what was Leonard's aim, to hear the music itself. Given the unsophisticated tools at his disposal—a Speed Graphic camera and the couple of spotlights he could afford—the immediacy of these photos and the capture of the play of light are remarkable. There's a primal quality to the photo of Buddy Rich who seems to be saying "talk to me baby!" as he looks gleefully, lovingly, at his drums. Double-paged portraits of drummer Art Blakey in Paris 1958, percussionist Candido Camero—still going strong at 90—in New York in 1954, and a beautiful shot of singer Ella Fitzgerald with rivulets of silvery sweat running down her face are most affecting.

Many of Leonard's best photos were taken offstage: the leopard-like, age-marked hands of trumpeter Doc Cheatham, seemingly holding crystals of light in his hands; tenor saxophonist Ben Webster framed in the doorway of a shabby building, legs apart, tenor clutched in right hand and looking for all the world like a gunslinger entering a saloon; violinist Stephane Grappelli and pianist Oscar Peterson smiling over a bottle of wine which won't stay corked for long, and a touching snap of Fitzgerald and bassist Ray Brown slow-dancing in a Paris club in 1958.

Leonard was a friend to these musicians and their obvious comfort with his presence resulted in pictures of truth, sincerity and tremendous humanity.

There are no photos from the 1970s and only a couple from the end of the 1980s, years in which Leonard lived in Ibiza, far from the music he loved so much. Two informative essays bookend the collection of photographs. Journalist and film maker Reggie Nadelson provides a summary of Leonard's life and career, while documentary film maker Leslie Woodhead's contribution offers a revealing portrait of Leonard at work, with the man himself talking in some detail of his method and philosophy. It may be encouraging for today's generation of photographers to learn that Leonard totally embraced digital photography, describing Photoshop and computer technology as "a Godsend." A truly fantastic shot of singer Frank Sinatra on stage and another of alto saxophonist Cannonball Adderley in the studio were only possible to reproduce with the aid of this technology. "What matters," Leonard states, "is the image you end up with. Not what you used to get it or how you produced it."

Herman Leonard died on August 14, 2010, though he lived just long enough to see this book go to press. Jazz is a beautiful testament to one of the 20th century's greatest photographers and an unmatched visual history of the musicians, and of those years, that still resonate so strongly today.

< Previous

Organic

Next >

Cape of Storms

Comments

Tags

Herman Leonard

Book Reviews

Ian Patterson

United States

Miles Davis

Dizzy Gillespie

Charlie Parker

Dexter Gordon

Bud Powell

Buddy Rich

Art Blakey

Ella Fitzgerald

Doc Cheatham

ben webster

Stephane Grappelli

oscar peterson

Ray Brown

frank sinatra

Cannonball Adderley

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.