Home » Jazz Articles » Interview » Wardell Gray, "Forgotten Tenor:" An Interview with Filmm...

Wardell Gray, "Forgotten Tenor:" An Interview with Filmmaker Abraham Ravett

[This is one of two interviews and an article intended to bring readers' attention to the revered but neglected tenor saxophonist, Wardell Gray, whose brief career spanned the transition from swing to bebop and whose life was cut short by sudden and tragic circumstances.]

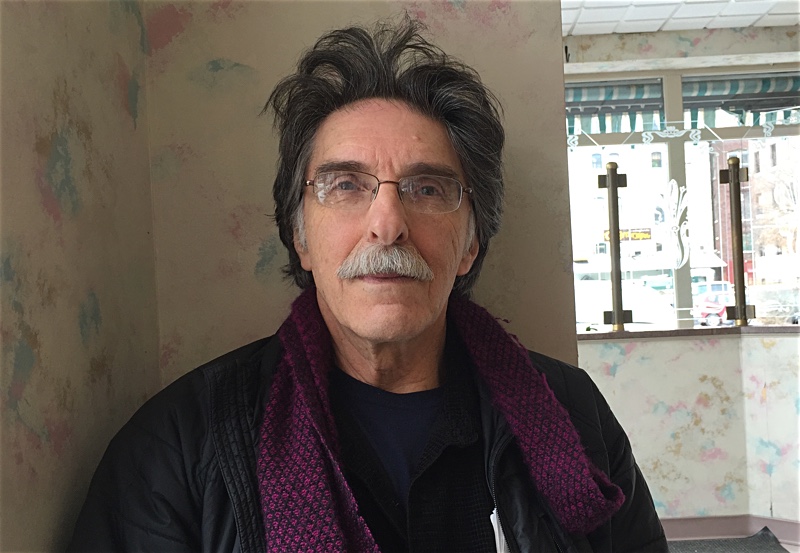

Swing and early bebop saxophonist Wardell Gray, despite exciting beginnings, had for all practical purposes vanished from the jazz radar until filmmaker Abraham Ravett was struck by recordings of Gray on the radio and decided to make a documentary about him which was released in 1994 under the name Forgotten Tenor. Since the release of the film, there has been a resurgence of interest in him but not nearly as much as his small army of cohorts and aficianados feel he deserves. The film raises more questions than it answers. In search of understanding about why such a prodigiously talented and productive musician as Wardell Gray became relegated to the back burner, All About Jazz looked up Ravett, resulting in the following interview with him.

Background of the Film Forgotten Tenor

All About Jazz: What interests and circumstances back in the 1990s led you to do a documentary about Wardell Gray?

Abraham Ravett: I finished the film in 1994, and it took me at least 3 years to finish it. I've always loved blues and jazz, and around 1990, a local jazz radio station host played about an hour and a half of this great tenor player. I thought, "Who is this guy? I never heard of him." So I called up the station and found out who he was. It was Wardell Gray. I was really intrigued by the fact that there was this spectacular musician I never heard of. I've always been interested in unheralded lives, not just in music, but in a variety of fields. So that's how it began.

I then started an exploration about "Who is this guy? Where did he live? Where did he come from?" I started on a journey to find out about him. At that time, I was working with 16 millimeter film. I had to carry a lot of equipment around with me, a 16 millimeter camera and a reel to reel tape recorder, lights, and so on. I began the project on my own and eventually got some financial support from several organizations.

At one point, I heard about something called Snader Telescriptions. They were the precursors of today's music videos. They were short film clips that were played in the equivalent of juke boxes. People inserted a coin, and they could see and hear different groups perform for a few minutes. In the 1940s and '50's there were a lot of these Telescriptions with jazz groups. There were several of them with the Count Basie Sextet during the time that Wardell was working with them. I was lucky enough to locate a collector in New York City who was nice enough to let me borrow and copy his 16 millimeter prints. As a result, I had a foundation of these four Snader telescriptions, and they gave me a way to begin to think about the musicans Wardell played with. At the time, the Sextet consisted of Basie, Wardell, Clark Terry, Buddy DeFranco, drummer Gus Johnson, bassist Gene Lewis, and rhythm guitarist Freddie Green. I started tracking down people, beginning with those on the film clips, which were really the cornerstones of the film. I made it a point to include one with Helen Humes singing " I Cried for You ," which featured a solo by Wardell. That clip gave me the pulse, to really look at him, to hear him with his colleagues, to really get a sense of his presence.

AAJ: You really brought Wardell's music to life in the film. But why did you include all the clips of you calling people and setting up the equipment that are usually omitted from films?

AR: It was based on the evolving form of non-fiction filmmaking that I was very interested in at the time. I wanted it to be more than an expository work. I wanted it also to be reflexive. I wanted to acknowledge the means of production and my own subjectivity in terms of who was making this film. I realized as I was editing the film that it was not going to be a work that was readily accessible, not something for television and such. As soon as I put in the entire 13 minute Charlie Parker-Wardell Gray "Lullaby in Rhythm" interlude with shifting gradations of color seen on the screen, I knew it wasn't going to be a popular documentary film.

I teach film and photography at Hampshire College and therefore, am not dependent on making a living from my personal work. as a result, I give myself a lot of creative flexibility in every project. i made this film the way I wanted to, a 2 hour and 16 minute homage to this unheralded musician that is formally challenging in its structure. It asks for the viewer to carefully attend and participate in its unfolding.

Has Wardell Gray Really Been Forgotten?

AAJ: The interviews with people who knew Wardell were fascinating, and the musical excerpts with him show what an extraordinary musician he was. So let's talk about Wardell himself. The main question that comes to mind is why he was forgotten. He was one of the most outstanding jazz musicians of the time (1940s -50s), and some of them died young, as he did, like Charlie Parker, but the others like Parker became legends. Wardell was one of the best among them and played often with the top-of-the-line swing and bebop groups. Why didn't his recordings and his legacy get passed on to subsequent generations of musicians and listeners?

AR: I would argue that the idea of "forgotten" is relative. While I was making the film, I was teaching at Hampshire College. It's part of a consortium of five colleges in western Massachusetts. As it happened, Archie Shepp taught for many years at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, which is in the vicinity of where I teach. I contacted him and told him I had acquired some footage of Wardell and invited him to a small screening room at Hampshire College where I projected the Snader Telescriptions featuring Wardell. Archie was sitting there, and when he saw each and every one of the film clips, he asked me to show them again and again. He loved them. Wardell was his inspiration and hero. So the idea of someone being "forgotten" is relative. Shepp, and a lot of other musicians I interviewed, remembered Wardell and acknowledged his influence.

AAJ: But Wardell does not come up in conversation among jazz fans the way that, say, Archie Shepp does.

AR: But a surprisingly large number of musicians do know about him.

AAJ: The musicians you interviewed all knew of him personally and performed with him. On a more general level, most of us know about Wardell only as a mysterious figure who passed in the night. Given his remarkable ability, whom he worked with, and the recordings we have of him, he is surprisingly relegated to the back burner in jazz circles.

AR: I'm not trying to say he is a famous figure in jazz. But he is well-known among musicians of his time and later on as well. His "disappearance" may partly be a question of his early and abrupt death. He died at age 34. He didn't have a chance to accumulate a full legacy.

AAJ: And, unlike Charlie Parker, who died at 35, he didn't leave a large body of recordings as a leader. And he was not an innovator of a new musical idiom.

AR: We do have some important recordings by him. I don't have his full discography in front of me. My website has a very extensive discography of his work.

AAJ: I did an informal search of your discography and several others on the web, and yes, he made a substantial number—at least fifty recordings that I could count—with some of the top big bands and small groups of the time, but only a few -maybe ten -as a leader, most notably with the Wardell Gray Quintet. To me, from what I've listened to, the quality of his playing is so remarkable that he should have developed a big fan base. But he may have been one of those great musicians like Tadd Dameron who fell under the radar.

AR: Interest in Wardell keeps popping up over and over again. Richard Carter in the U.K. has been working on Wardell's biography for many years. There's a lot of information and memories about Wardell out there that he's collecting.

AAJ: The reason the neglect of Wardell is important is not because of fame and fortune but because there is so much great music and there are so many great musicians who get short shrift. The jazz community misses many wonderful listening opportunities because of that, not to mention the musicians who suffer anonymously and many of whom die destitute and forgotten. I recently interviewed Paul Combs, who wrote a fine biography of Dameron, who also was largely forgotten, even though he had a huge influence on his contemporaries.

AR: Yes, we do have to take the time to bring such musicians to everyone's attention.

Wardell Gray: Person and Musician

AAJ: Let's discuss Wardell Gray, the person, whose life had a tragic ending which we'll take up a little later. From your film, I got the impression that he was a mystery man, a wanderer, a not uncommon impression or stereotype of the uprooted African American male persona. Do you think that was how he really was?

AR: No, I really don't think so. Wardell was married and devoted to his family. Dorothy Gray, his last wife, said he was really connected to family and cared about them. He was well read and well educated. But he was a travelling musician. He had to go where the work was. Even today, musicians have to make a living, they have to travel, and it creates tensions within their families and with others who are close to them.

AAJ: Yes, and as you point out in the film, he wrote many letters home, and often expressed regret that he could not be there. He emphasized in some of his letters that he needed to travel because he wanted to be a good provider for them. And he was a very well-liked guy.

AR: I never had the impression that he was a loner. Based on the people I spoke with, he was well-connected to relationships. He didn't come off to them as someone who was withdrawn or obscure or didn't care about anything except the music. He was very connected to others. At least, that was my impression from those with whom I spoke.

Wardell's Tragic and Unexplained Death

AAJ: Perhaps his drug-related problems towards the end of his life may have retrospectively colored the overall picture of who he really was.

AR: I have to tell you that when I made the film, I really tried very hard not to sensationalize the whole aspect about drugs and the circumstances of how he died. I emphasized his life and work. For example, in my conversation with Teddy Edwards, he spoke about the intimacy of his relationship with Wardell, although the tragic ending did come up. When I interviewed Clark Terry, he spoke passionately about his relationship with Wardell and told me he was really surprised when he found out that Wardell was hooked on heroin. But I wanted the film to relate to Wardell as a great musician and the legacy he left of his work and his relationships.

AAJ: Yet in terms of biography and history, coming to terms with the circumstances of Wardell's death is unavoidable. It's an unsolved gruesome mystery. In your film, the musicians who were around him explain his death as a drug overdose. But his body was found in the desert near Las Vegas, and his neck was broken. That suggests murder, although the coroner attributed the cause of death to "natural causes." It's hard to put two and two together here. Have you found out anything since you made the film twenty years ago that might provide some clarity?

AR: No, I haven't gotten any further clarification. It's one of those things that his closest intimates couldn't figure out. It's just one of those unsolved "cold cases." Who knows what happened? Unless someone eventually figures it out, it's more important to me to resurrect Wardell's presence and acknowledge his contributions.

Further Thoughts

AAJ: You are a film-maker and teacher by profession, and a number of your films are about the Holocaust. Do you see some connection between the persecutions of the Nazi era and Wardell's life and those of other jazz musicians under segregation?

AR: I don't think so. I just happen to have multiple interests. I've always loved music and at times have aspired to being a musician. But maybe there is one connection that I would make: the idea of resurrecting and paying tribute to unheralded lives, lives that are extinct. My family included victims of the Holocaust whose lives were extinguished or those who managed to survive. I've made several films that among other themes, pay tribute to these members of my family. That may be a thread connecting the Wardell Gray film and my other work. I just finished a film about Oliver Nelson's Blues and the Abstract Truth (Impulse, 1961) recording session. It's one of the greatest albums ever made. Like Wardell, Oliver Nelson should be better known.

AAJ: In the film, you don't bring up Wardell's famous saxophone duels with Dexter Gordon. I wonder why you didn't take up Dexter's interactions with Wardell, although for one thing Dexter passed away shortly before you made the film.

AR: I do have a picture of Dexter Gordon in the film. I tried to get more information about Dexter vis-à-vis Wardell, but nothing turned up. Also, there were cost considerations in purchasing the rights to Dexter Gordon's recordings and so on. I do mention the Dexter Gordon -Wardell Gray collaboration in the film, but for practical reasons, I couldn't include more. Also, my initial focus was on the Count Basie Sextet in which Wardell participated, and then I branched out from there to other musicians who were still around.

AAJ: What more would you like to tell us about Wardell and the film?

AR: Importantly, since it was released, this film has had a life of its own for twenty years. I keep getting inquiries from all over the world. Wardell's presence and influence continues to linger. What lingers is not only his musical legacy but also what a wonderful person he was to the people around him who cherished him as a musician, friend, husband, and father. And like record producer Bob Weinstock said in the film, we're all still feeling the loss of so many of the great musicians who in that era, died at such a young age.

By no means could I cover everything about Wardell in Forgotten Tenor. What I hope it will do, is stimulate people to listen to Wardell's recordings, learn more about him and fill in some of the gaps in what the film couldn't cover. He doesn't have to remain forgotten.

Editor's Note: Professor Ravett's website contains information and a film clip . The DVD is currently available only directly from him. His contact information is also provided there.

< Previous

I'll Be Home For Christmas

Comments

Tags

Abraham Ravett

Interview

Wardell Gray

Victor L. Schermer

United States

Count Basie

Clark Terry

Buddy de Franco

Gus Johnson

Freddie Green

Helen Humes

archie shepp

Tadd Dameron

Teddy Edwards

Dexter Gordon

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.