Home » Jazz Articles » Opinion » Why Is Jazz A Dirty Word?

Why Is Jazz A Dirty Word?

Here are the top five reasons why people think and feel this way, and have already written jazz music off:

1) It's old and outdated music;

2) It's way too dissonant and too far outside the normal harmonic box;

3) It's insider musical language that only other jazz musicians can understand;

4) It's boring, with 10 minute solos featuring musicians playing strange sounding scales;

5) It's music played by a bunch of artsy weirdos and drug addicts; you have to be using drugs/alcohol to really appreciate it.

All these criticisms contain valid and legitimate reasons why the general public feels the way it does about jazz music. Let's take a closer look at these reasons.

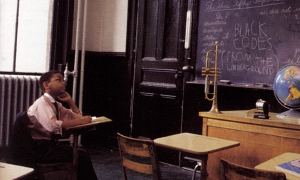

For many today, the word jazz implies old outdated music. They consider it music of the past, and that its value and relevance has, for the most part, faded away. One of the things that is responsible for this misconception is that many purist jazz musicians today insist on only playing old jazz standards, from the 1930s and '40s. They and their music seem to be trapped into an historical box, much like many church folk who insist on singing and hearing nothing but old hymns from 100 years ago. Instead of writing and playing new jazz music, these jazzers keep on playing songs that were written "back in the day." Of course, the way that jazz is depicted in movies and on the big screen plays a large role in typecasting jazz music as old, out of touch, and therefore not relevant.

Other jazz artists, as their jazz language develops, choose to move further outside the harmonic box by writing and performing jazz that contains so much dissonance that only other jazz musicians can appreciate it. Here is how the dictionary defines dissonance:

Noun: inharmonious or harsh sound; discord; cacophony.

a. a simultaneous combination of tones conventionally accepted as being in a state of unrest and needing completion.

b. an unresolved, discordant chord or interval. Related words for dissonance are: disagreement, dissension, noise, racket.

To the average listener, it's almost as if jazz musicians just decided to be different and break all the accepted rules of harmony that classical music contains. And, on the surface, it appears that the more dissonance and unresolved chords a jazz composition includes, the better jazz composer you are.

Of course, there are many accepted rules that apply to classical music, but as music history has documented, with the dawning of the Romantic era, composers began breaking out of the harmonic box more and more, using much more dissonance in their compositions. Many of the musicians who have been trained in classical music that switched to playing jazz can testify how liberating it can be to break free of all of classical music's harmonic rules. But, let's face it: we've all heard jazz music that breaks so many conventional harmonic rules and is so dissonant that it can get on one's nerves. If there is too much tension, and harmonic clashes that are never resolved, it can leave the average listener hanging and in need of a sedative. This has been a crucial factor in turning most people off to enjoying jazz.

Of course, those who study jazz music, and are initiated into hearing more dissonance, grow more accustomed to hearing heavy dissonance and appreciating it. It then becomes jazz insider language that only the educated ear can appreciate. This jazz insider language has turned many listeners off, and has been a major factor in giving jazz a bad reputation. To the uninitiated ear, heavy dissonance used in a song isn't beautiful—it's ugly noise that irritates.

I heard a quote somewhere, where a person shared that they listened to a recording by saxophonist John Coltrane, and they thought it sounded more like a parakeet crapping out blood. That's very sad, because Coltrane was an incredible jazz musician, and viewed his playing in a spiritual way. But many have also complained about Charlie Parker ("Bird")—that his music was nothing more than noise.

Then there's those 10 minute solos, where a jazz musician plays every dissonant scale he's ever been taught, and then he plays them backwards in retrograde motion, and wonders why no one appreciates his soloing except for a few other jazz comrades. This can come across as arrogant to many listeners, because they feel almost like the soloist is saying "Gee whiz, just listen to what I can do on my instrument"! This tends to take the focus off the music, and the emotional feel of the music and place more emphasis on the individual soloist as a performer. Usually, when jazz musicians go off on lengthy solos, the listening audience shifts back into more of a spectator role, and the technical expertise of the performer tends to overshadow everything else. Unfortunately it is only other jazz musicians who really know how much work and dedication is involved developing technique that really can appreciate it.

There are, however, those times when a jazz musician plays a solo that lifts and transports both the performer and listeners to a sublime level. There is the perception—in the audience—that the soloist is genuinely expressing and responding to how he feels about the music he is playing, and that he has something deeply important to communicate and share with the listeners. Without allowing time and space for jazz musicians to have the opportunity to freely express themselves would only serve to take one of jazz's most precious elements away—the freedom to improvise.

Jazz musicians and jazz historians have always valued free improvisation as a unique element in their music. Allowing space for individual musicians to express themselves freely with on the spot improvisational soloing has always been the norm. Freedom to choose, freedom to play, and freedom to improvise...freedom is what jazz is all about. But the original roots of jazz language stems from the musicians collectively sharing an ecstatic experience, where they are lifted out of the ordinary state of mind and the music seems to just flow freely out of them. There are many examples. in the history of jazz, that document this ecstatic nature and its effects on jazzers and listeners. New Orleans old timer, Jim Robinson, once shared how the ecstasy used to flow on the bandstand on certain nights: "If everyone is frisky, the spirit gets to me and I can make my trombone sing!" Singer Ethel Waters testified that certain stride pianists ..."stirred you into joy and wild ecstasy," and drummer Billy Higgins once said, "Music doesn't come from you, it goes through you!"

Of course, we've all seen the old black and white movies picturing jazz musicians all strung out on drugs in a smoke filled club, with half-naked ladies, where the audience is stoned out of their minds as the music plays. A brief survey of jazz history easily reveals that many of the great jazz musicians used drugs and were in fact heavily addicted to them. Of course, drug use and addiction is unfortunately a fact of life in modern society, and for many musicians in every style of music...not just jazz musicians.

So far we have addressed, in detail, the main reasons why the average listener doesn't like jazz. But there are other reasons that go even deeper. Many people might hate jazz music because many of the jazz musicians who played it and wanted to preserve it changed its original context. Jazz music shifted from being music that was to be enjoyed and danced to, into music that was to be instead appreciated as an art form. Music for the brain, not for the soul—the implication being that a listener must acquire a taste for jazz music. You might not like hearing it at first but stick around...it will grow on you and you will begin to understand it!

Jazz pianist (and respected spokesman for jazz), Ben Sidran sheds some brilliant light on the true roots of jazz music, when he said, in a recorded dialogue/narrative that ..."if you had been in a Harlem jazz club in 1927, you would've seen some people dancing! This music [jazz] was meant for dancing!" He goes on to point out that many of the pioneers in jazz., such as Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, all played their music for dancing. Even more profoundly, Sidran went on to make the case that, in our ancestral human history, rhythm proceeds even language. That hundreds of thousands of years ago, early humans would gather around a fire and dance to a groove before they even had a language they could speak.

That jazz music has, at its very roots, a strong rhythmic element is a well-established fact. But probing deeper into our history as human beings reveals a universal need to have an ecstatic experience—to step outside of ourselves, so to speak, and dancing to a beat is one of the most powerful methods for achieving this. This ecstatic element was another key ingredient that helped create jazz music that the common listener loved, because it made listeners want to get up and dance. The unique swing rhythmic factor in jazz is closely connected to body and dance movement. To illustrate this point, imagine back to when you were a child, joyfully skipping on the playground in a rhythmic pattern. This skipping is rhythmically very similar to the swing elements present in jazz music.

Dancing to music or even tapping your foot also takes the listener out of the role of just being a passive spectator to being an active participant.

Another significant element that help make jazz unique is rhythmic syncopation. Syncopation in music includes using a variety of rhythms which are, in some way, unexpected in their deviation from the strict succession of regularly spaced strong and weak beats. Extra stress and emphasis is placed, and accented on beats out of the norm, adding elements of surprise and playfulness in jazz. Much like children at play, spontaneously and playfully making something up on the spot, jazz has always had this quality at its core. Once again, the dictionary defines the word playful is:

Full of fun and high spirits; frolicsome or sportive: a playful kitten. 2. Humorous; jesting.

Surprise and playfulness in music is fun, can help relieve monotony, and has always been a part of jazz composition. However, in the early 1940s, jazz musicians started looking for new directions to explore. A monumental paradigm shift occurred within jazz, and a new style of jazz was born, called bebop. It had lightning-fast tempos, intricate melodies containing angular intervals, and much more dissonant and complex harmonies. Bebop was considered jazz for intellectuals. No longer were there huge big bands playing jazz music in dance halls, but instead smaller groups that played this new form of jazz for a listening, rather than dancing, audience. Many of the playful elements disappeared, only to be replaced by a more serious focus on technical expertise, and the analysis of jazz as an art form.

Today, the typical listener really enjoys music that has roots that stem from jazz—but just don't call it jazz. People still want to dance to music and be participants, not just spectators. So rock music, R&B and rap dominate the popular music listened to and purchased by music lovers today. Ironically, all these musical styles were birthed right out of jazz. They all have a strong rhythmic element, with plenty of syncopation.

Jazz historian Joachim E. Berendt, in his 1952 book, The Jazz Book offered the following observation about how jazz has continued to evolve: "Today, the jazz musician must be fluent in many styles, not just one...one of the main reasons why rock elements can be so smoothly integrated into jazz is that, conversely, rock has drawn nearly all its elements from jazz—especially from the blues, spirituals, gospel songs, and the popular music of the black ghetto, rhythm and blues and soul music." Drummer Shelly Manne once said, "If jazz borrows from rock, it only borrows from itself"! Saxophonist/educator Dave Liebman shares that "To me 'fusion' doesn't mean a rock beat or an Indian drum. It's a technical word that means to put together...of course all music is a fusion...now of course it's commonplace to put together styles; everybody does this every day" (Downbeat Magazine January, 2011). Bassist/educator Dr. Lou Fischer states that "Fusion, to me, represents a juxtaposition of any and all genres of music. In the broadest sense, we play fusion music any time we play jazz. Even in straight-ahead jazz, there's a fusion of all elements—classical, African traditions and rhythms, Brazilian music." So we can rejoice that the true ingredients in jazz music continue to have a major impact and influence on many styles of music.

Educating our present day culture about jazz music involves shattering the many misconceptions that exist about jazz music. A great place to start this process is by pointing out that most popular music being played today is derived from jazz and the blues. Jazz education is playing a critical role in helping bring this about. Jazz programs in public schools are helping to develop new jazz musicians from the younger generations, and to garner a greater appreciation for jazz. But it will also involve jazz musicians taking a hard look at the many reasons why people say they don't like jazz, what made jazz a dirty word, and doing some serious soul-searching. Being sensitive to these reasons will take much time, patience, and persistence, but can help bring about more favorable acceptance and greater appreciation for jazz. My vision for jazz music in the future is a world where jazz, (in all its many flavors) will be the most popular music in the world and even the word jazz itself will be used, understood, and respected in a sacred way.

< Previous

Appreciation

Next >

Alone At The Vanguard

Comments

Tags

Opinion

David Arivett

United States

John Coltrane

Charlie Parker

Jim Robinson

Ethel Waters

Billy Higgins

ben sidran

Louis Armstrong

duke ellington

Count Basie

Shelly Manne

Dave Liebman

For the Love of Jazz

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.

All About Jazz has been a pillar of jazz since 1995, championing it as an art form and, more importantly, supporting the musicians who create it. Our enduring commitment has made "AAJ" one of the most culturally important websites of its kind, read by hundreds of thousands of fans, musicians and industry figures every month.